Libereco: no improvement in human rights situation one year after sanctions were lifted

One year ago, on 15 February 2016, the EU Foreign Affairs Council decided to lift most of the sanctions against Belarus. This decision was preceded by a reduction in visible repression in Belarus since the summer of 2015, through the release of political prisoners and relatively peaceful presidential elections. As Russia’s aggressive foreign policy and the resulting instability in Ukraine remain a grave concern for the EU, Belarus tries to be a showcase of stability and moderation in the region. The monitoring carried out by Belarusian and foreign human rights NGOs shows, however, that one year on the human rights situation in Belarus is still bleak.

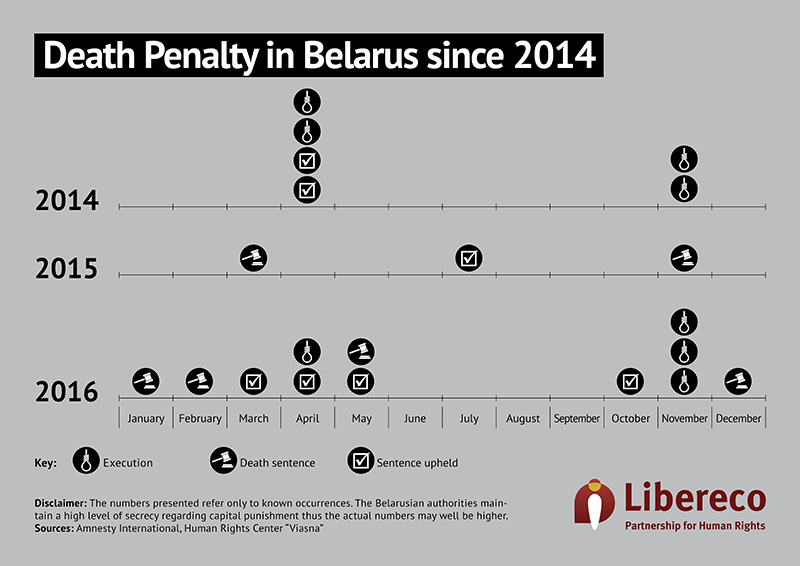

Together with the Belarusian human rights organisation Viasna, Libereco – Partnership for Human Rights monitored human rights violations in Belarus during the first 100 days after the lifting of the sanctions. The report “100 Days of Belarusian Rule of Law”featured developments in the field of freedom of assembly, speech and association, the death penalty, police violence, and police impunity. It concluded that optimism about the human rights situation in Belarus was not justified. Repression continued, although it took on less visible forms. Political imprisonment and large scale violence against demonstrators became less common, but fines to curtail the right to peaceful assembly increased sixfold. The use of capital punishment even increased during the monitoring period. By handing down a death sentence the very day the sanctions were lifted, Belarus showed no interest in improving the human rights situation. One year later, many of the trends visible in the first 100 days have proved representative for the months to come.

Trends continue: substantial increase in use of death penalty and fines

The increase in the use of the death penalty in the last European country that applies capital punishment constitutes a major concern. Already in the first five months of 2016, more people had been sentenced to death and executed than in the whole of 2015. With a purge of death row in November 2016 - which ended the lives of three prisoners - and two more death sentences, 2016 became the most deadly year since 2008.

The trend to replace violence and imprisonment with less visible means of repression intensified. Viasna concluded in its 2016 analytical review that the year was marked by a nearly sevenfold boost in fines for exercising freedom of peaceful assembly and expression, totalling 484 cases. Recognising that fines are a less severe punishment than violence or imprisonment, it is still extremely difficult and not without risk to voice your opinion or gather publicly in Belarus.

The adherence to freedom of speech and association did not improve either. The fining of independent journalists and hindering them in carrying out their professional duties continued. Free-lance journalist Kanstantsin Zhukouski, fined and arrested several times throughout the year, is the most visible example of a practice that continues to hamper independent journalism. Moreover, not a single independent public association managed to register itself during 2016, testifying to the lack of freedom of association. This includes Viasna itself: since authorities retracted its registration in 2003, the organisation has had to operate on the fringes of legality.

Although the use of violence has declined markedly in favour of less visible forms of repression since 2015, cases of police violence continue to occur. A marked example was the case of paediatrician Dzmitry Serada, whose apartment was raided by masked police forces early one morning in August 2016. He was beaten and arrested. As the initial suspicion of having committed a non-violent crime proved unsubstantiated, Serada was released without charges – but only after he spent one day and night in jail without meals and suffering from concussion. The fact that his complaints pertaining to his treatment were rejected twice is testament to the widespread police impunity in Belarus. In an interesting turn of events, however, the Minsk Prosecutor’s office opened a criminal case against one employee of the Interior Ministery in January 2017.

New cases of political persecution

The considerable decrease in political imprisonment since the summer of 2015 did not signal the end of political persecution. 2016 was marked by several cases of politically motivated imprisonment or forced psychiatric treatment. Human rights activist Mikhail Zhamchuzhny and activist Aliaksandr Lapitski remain in detention, while blogger Eduard Palchys and anarchist and Critical Mass activist Dzmitry Paliyenka have received suspended sentences. Uladzimir Kondrus, who was arrested in June 2016 on charges of rioting during the December 2010 post-election protest, was sentenced to 1.5 years of personal restraint and forced outpatient psychiatric treatment. Belarusian human rights organizations recognise Kondrus, Zhamchuzhny and Lapitski as political prisoners.

In its analytical review, Viasna sees “no systemic changes aimed at a qualitative improvement of the human rights situation in the country” on the part of the government. Despite more covert forms of repression, as well as Russia and Ukraine dominating the Western agenda, the human rights situation in Belarus continues to merit public scrutiny.